AI Isn’t a Product: Rethinking AI Product Strategy to Avoid the Internal Innovation Trap

Artificial intelligence has moved beyond experimentation. Large enterprises are now embedding it across supply chains, procurement, and finance. Some position generative AI as the core of autonomous operations in logistics and planning. As these efforts scale, the definition of an AI product strategy has become increasingly ambiguous.

Internally developed AI tools, such as sourcing optimisers or forecasting engines, are often described as products and presented as evidence of transformation. While these systems may enhance productivity or decision-making, they do not automatically qualify as strategic innovation.

The underlying assumption is that any technically advanced use of AI within the organisation represents strategic progress. This article, part of 3nayan’s series on AI, challenges that view. An AI initiative cannot be considered a product until it contributes to competitive advantage, customer value, or monetisable outcomes.

This is not a discussion about commercial AI products. It is a closer look at how internal deployments are often mistaken for strategy, and what it takes to correct that framing.

Equating Tools with Products

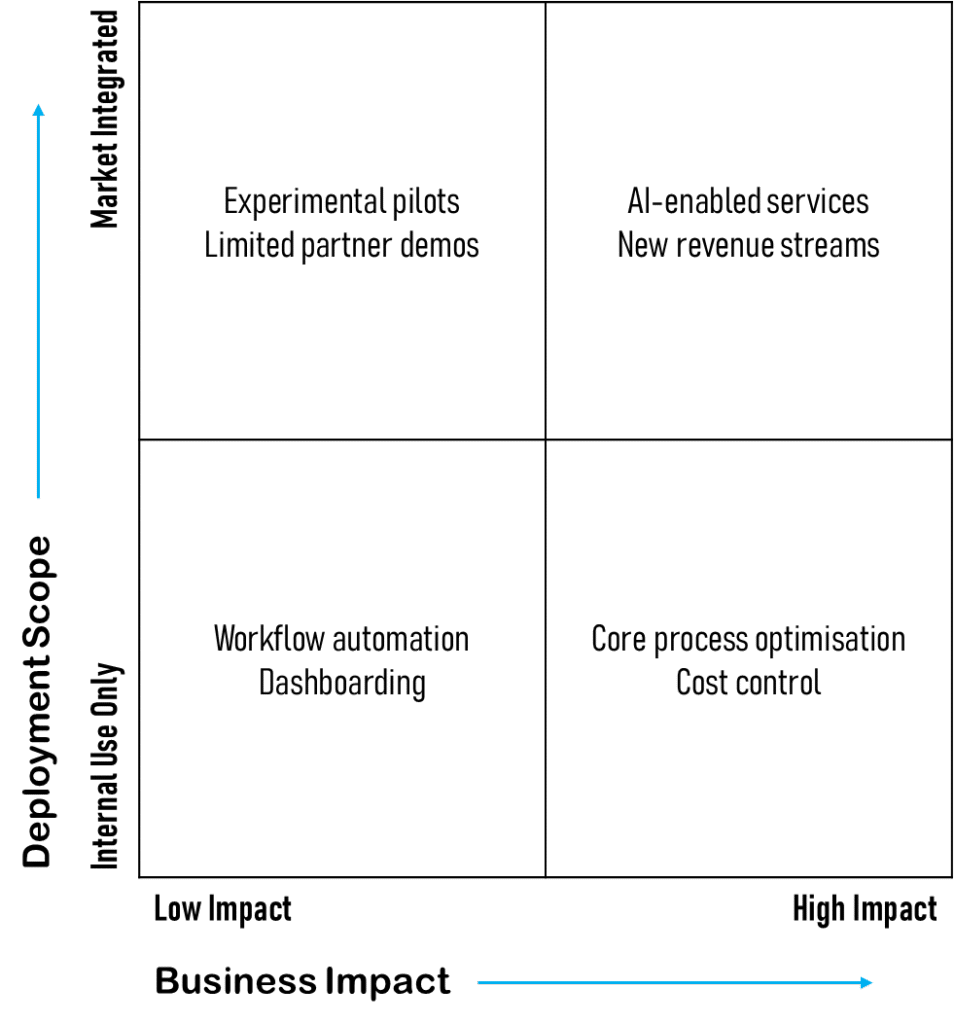

Across industries, companies are increasingly describing internal AI deployments as “products.” These typically include tools to automate procurement tasks, generate reports, or assist employee decision-making. While such implementations improve efficiency or reduce costs, they are often mistaken for strategic outcomes.

The distinction lies in intent. Internal AI tools are built to optimise operations, not to deliver strategic outcomes. This mirrors the early digital transformation wave, where many initiatives failed by prioritising efficiency over impact. AI now risks the same pitfall, with internal gains often misread as enterprise innovation. A true AI product strategy must target growth, profitability, customer value, or market advantage.

As an example, JPMorgan Chase has committed over $18 billion to technology, including more than 100 AI tools and a generative AI platform deployed to some 200,000 employees. These tools are said to target internal workflows such as research, coding, and task automation. While they aim to improve productivity, their strategic value depends on whether they unlock new capabilities that enhance the bank’s competitive position or client engagement.

The risk lies in melding deployment with differentiation. AI becomes a showcase rather than a capability. Here, internal efficiency provides a proxy for innovation, and organisations risk mistaking activity (input) for progress (outcome). In such cases, the enterprise may accumulate tools without building advantage.

What a Real AI Product Strategy Looks Like

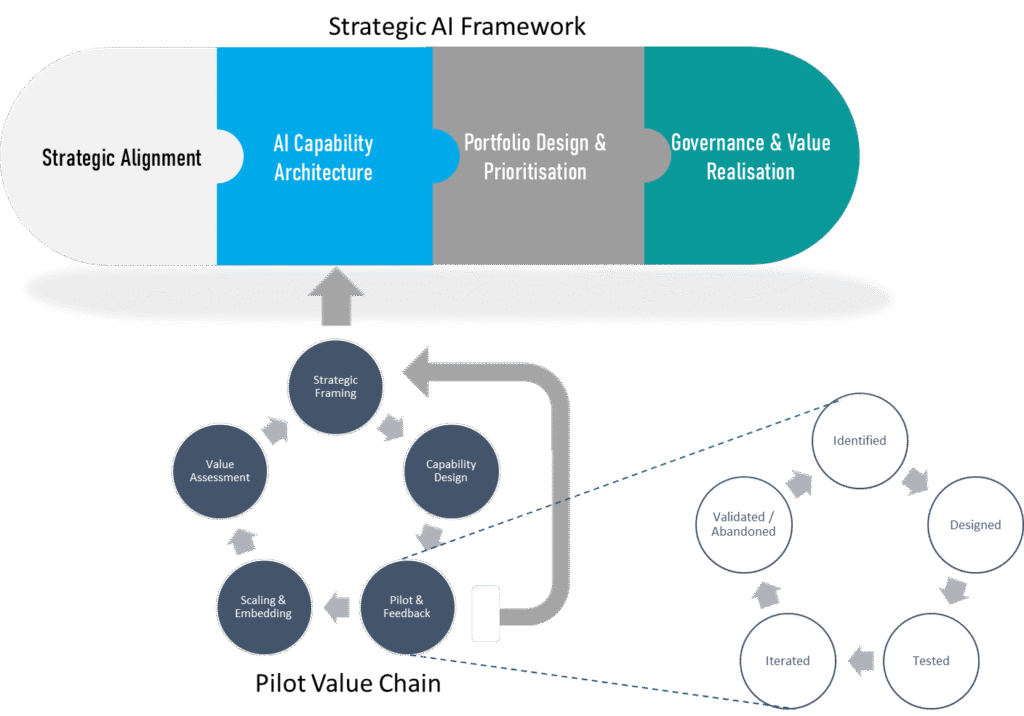

Many internal AI tools begin with a narrow goal, e.g. automate a task, reduce manual effort, or generate faster insights. While being legitimate outcomes, they remain confined to internal process improvement. A genuine AI product strategy, however, should start with a different premise as well as a different promise.

Asking what can be automated is looking at an enterprise with an AI hammer in hand. Instead, the strategy needs to ask what is the business is trying to achieve. It could be faster growth, margin improvement, better customer outcomes, or entry into a new segment. AI is then to be applied to these strategic objectives, not as a demonstration of capability, but as a means to unlock new value.

Basic Tenet of an AI Strategy

Therefore, the core of an AI product strategy lies in whether the solution scales beyond its initial use case. the pertinent questions to ask are:

- Can it be embedded in customer workflows?

- Does it enhance the firm’s market proposition?

- Is it part of a repeatable, defensible capability that can be industrialised and contributes to growth?

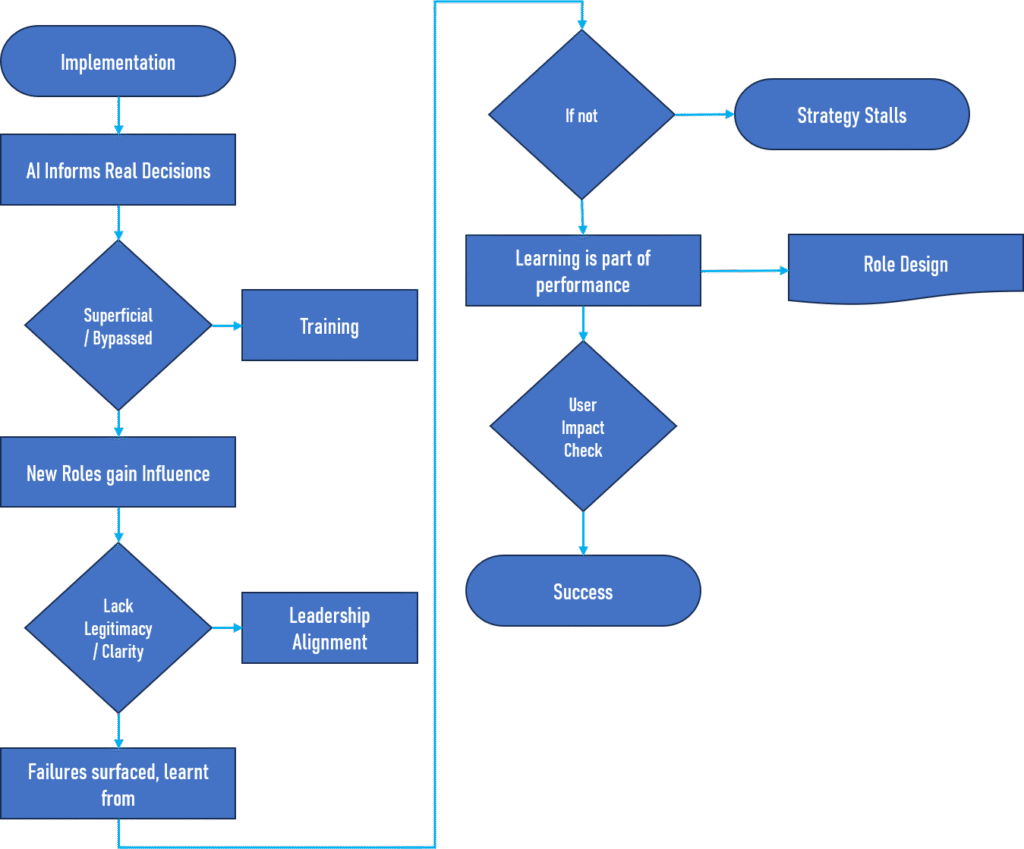

Moreover, strategic AI efforts tend to follow a different development path. They are designed with feedback loops (as in the above diagram), tested with real users, and supported by cross-functional teams that include product managers, domain experts, commercial owners and hopefully some customers.

These cause AI to be treated not as a technology deployment but as a strategic lever. Ultimately, the hallmark of a real AI product strategy is not how advanced the model is, but how clearly it aligns with the organisation’s competitive ambition.

From Internal Gains to Market Impact: Reframing AI Product Strategy

Enterprises often equate internal adoption with success. A model that assists a team or automates a process is quickly positioned as a product. However, the created capability must integrate with external stakeholders to deliver its potential and realise value.

This external integration makes the AI initiative strategic. That may mean powering a customer-facing workflow, enabling self-service through intelligent systems, predicting through a vendor’s supply chain or forming the core of a monetisable service. This shift from internal optimisation to market relevance requires a change in how AI is framed, built, and measured. It is not enough for the model to function. It must be embedded where real outcomes occur, across external stakeholder integrations and touchpoints, transactions, and decisions that matter to the business. This visibility to users, and value in their context makes the AI a strategic asset.

Integrating AI: Strategy is Change Before It Is Technology

For AI to truly become a strategic asset, it must be absorbed not just into systems, but into how the organisation works and accepted by the organisation. More than new tooling or talent, it requires a shift in how people make decisions, how teams collaborate, and how value is defined and measured.

The success of an I framework depends less on the models and more on the humans around them. The challenge is anthropological as much as it is technical. AI disturbs existing hierarchies of expertise, reconfigures workflows, and introduces unfamiliar forms of agency. This can create resistance, misalignment, or even quiet disengagement.

To manage this change, the organisation needs to go beyond a communication plan, a series of town halls, or training modules. It must be embedded into the strategy itself. That means identifying how roles will evolve, what kinds of decisions will shift, and where new skills or interpretations will be required. Teams need clarity on their contributions will need to align with the new enterprise strategy, and thus change. Performance systems must evolve accordingly to capture the changed set of measurement criteria.

Cultural Signals That AI Integration Is Taking Hold

Introducing AI also calls for a rethinking of organisational language. Terms like “adoption,” “acceptance,” or “enablement” can be misleading. They suggest a one-way transition. In reality, successful AI integration requires co-creation—between builders, users, and stakeholders. It is not about using a system, but about reshaping how work gets done.

Ultimately, a mature AI product strategy is inseparable from organisational change. The technology may be intelligent, but its impact depends on whether the organisation can become intelligent in how it adapts. This is where transformation either embeds—or stalls.

…So Stop calling it a Product until it performs like one

Enterprise AI has moved past experimentation. The question for you, is whether it will move past being internally focused in your organisation. Tools, copilots, and assistants may automate tasks, but without a defined and measured path to real users, customer value, or market differentiation, they remain operational artifacts—not strategic assets.

A true AI product strategy is required for an organisation, and this strategy needs to begin not with a model, but with a business outcome. It requires rigour in framing, cross-functional execution, external stakeholder validation and critically, an organisation that is prepared to absorb change. When roles evolve, when learning is rewarded, and when feedback loops drive design, AI becomes how the enterprise competes.

Many companies today are building. Fewer are integrating. Even fewer are aligning AI with how they create and capture value. Closing that gap is not just a question of technology. It is a question of structure, incentives, language, and leadership.

Until AI changes what your customers experience—or what your competitors cannot replicate—it is not a product. It is potential.

Check out the case studies below. Please note, the case studies and the content have been generated by an AI.